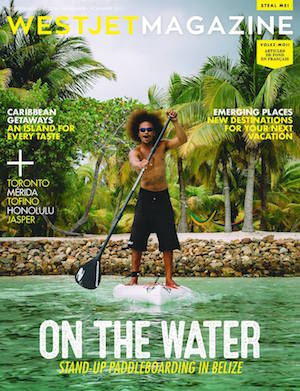

We are thrilled to be featured in this article in the November 2017 edition of the WestJet Magazine!

The article highlights our multi-day stand-up paddleboarding (SUP) trips in the beautiful Southwater Caye Marine Reserve. We teamed together with Norm Hann Expeditions to create the ultimate lodge to lodge Belize paddleboard experience for all levels. Norm Hann is one of the top SUP instructors in North America and has been working alongside our Belizean guides to bring you the unique Coral Islands SUP trip .

On this Belize SUP and snorkel adventure, you will explore the second largest barrier reef in the world and visit small islands including Tobacco Caye, Southwater Caye and Billy Hawk Caye.

Read more about travel writer Dan Rubinstein's experience stand-up paddleboarding in Belize on our Coral Islands SUP trip.

WestJet Magazine - Dan Rubinstein, Photos by Steve Collins

“Exploring Belize On a Stand-Up Paddleboard.” - November 1, 2017

Stay in the rainforest and in island cabins as you paddle your way through the South Water Caye Marine Reserve on an excursion with Island Expeditions.

Returning to Tobacco Caye

A steady easterly is blowing me away from South Water Caye, a small tropical island on the crest of Belize’s Southern Barrier Reef. I drive my blade into the turquoise water and propel my 12-and-a-half-foot-long stand-up paddleboard forward, aiming for a green smudge on the horizon.

Feet shoulder-width apart, knees slightly bent, arms rigid and hinging at the waist with each stroke, I’m trying to focus on technique—my instructor, Norm Hann, a Canadian paddleboard pioneer, could dash over and deliver a remedial lesson at any moment. But there are distractions: stingrays glide beneath me in the clear Caribbean Sea, pelicans swoop overhead and, though struggling to remain upright, I’m attempting to ride some waves.

Stand-up paddleboarding (SUP) is the fastest-growing water sport in the world, and the South Water Caye Marine Reserve is a perfect place to learn. Protected by the largest barrier reef in the Americas and scattered with sandy islands shaded by coconut-laden palm trees, the warm shallow sea is idyllic whether you’re on it or in it.

The wind is making this morning’s 10-kilometre open-water paddle to Billy Hawk Caye a little choppy, but I’m in good hands: British Columbia-based Island Expeditions has been guiding visitors in Belize since founder Tim Boys drove down from Canada with a kayak three decades ago and realized that the country’s pristine coral reef ecosystem was an untapped paddling paradise.

Paddling on Tobacco Caye

The company’s roster of kayak trips has grown over the years from a single winter tour to more than a dozen each season. In 2014, Island Expeditions hired Hann—who leads paddleboard expeditions and courses throughout Canada, and teaches others how to teach boarding—to help develop a SUP program for its Belize excursions.

Though paddleboading is the main event, the tour I’ve signed up for starts inland, away from the sea.

Less than an hour after landing in Belize City, I’m alone inside a screened-in jungle cabana at the Tropical Education Center, adjacent to (and owned by) the Belize Zoo. It’s humid, but breezy, and the savanna rings with chirps and calls. Island Expeditions, which built these cabanas and donated them to the centre, emphasizes conservation and education. Along with funding the education of local employees’ children, it’s the company’s way to give back to the country where its business has boomed.

The next morning, on the two-hour drive to the coast, our guide Onil Avilez gives our group of six an overview of Belize’s colonial history (independence from Britain came in 1981) and its easygoing, largely English-speaking kaleidoscope of Kriol, Maya, Garifuna, Latino and Mennonite communities. We pass orange groves and pineapple stands; clouds tumble down the green ridges that flank the highway.

In Dangriga, we drop our dry bags in a 25-foot outboard and, as the sky starts to spit, set out on the 30-minute passage to Tobacco Caye. The boat slams off and splashes through incoming waves, and the need for dry bags is quickly apparent. But it’s a refreshing drenching, and we’re piloted by the unflappable Captain Balls. “Best not ask how people around here got their nicknames,” I’m advised by multi-talented Belizean guide Kimike Smith, who is leading the tour alongside Hann.

Lounging at the Tobacco Caye cabins

When we dock in a deluge at the Tobacco Caye Paradise lodge, manager Doreen Castillo ushers us into the dining room, where a pot of tomato soup and platter of grilled-cheese sandwiches await. We’re at the northern end of a five-acre former fishing camp that’s home to about 30 people, a three-minute walk from tip to tip. The biggest danger, Smith warns, is falling coconuts.

After unpacking in my cabana, which has a hammock on a deck that’s suspended over the water, I return to the common room for dryland training. Since SUP-ing is so simple (i.e., stand and paddle), few people seek proper instruction, says Hann. He begins with the basics: a strong forward stroke. Though I’ve been boarding for nearly two years, fundamentals such as correct hand position (reach up and bend your elbows 90 degrees to find the right span) and an efficient “catch” (when you plunge the paddle blade into the water) are new concepts.

“It’s technical, like a golf swing,” says Hann. “We may have to break you down and build you back up.”

Paddling to Bird Island, near Tobacco Caye

Paddleboarding was born in the big waves of Hawaii, and one of Hann’s goals is to make us more comfortable in dynamic conditions. A canoe-loving high school teacher from Northern Ontario who moved to B.C. to become a wilderness guide, Hann rented his first board in Vancouver in 2008, then begged the shop to sell it to him. He has paddleboarded the 715-km Yukon River Quest race, paddle surfs the Pacific, and can SUP the West Coast Trail in a weekend.

But, wherever he paddles, whatever his pace, he loves that it’s a different perspective than sitting in a boat. You’re a small speck on the water, attuned to its rhythm. That’s the hook for many of us—once you find your balance on a paddleboard, the sport can easily become an obsession.

When our lesson finishes, I embark on a solo circumnavigation of Tobacco Caye. Tucked just inside the reef, the island is shielded from the pounding seas. I paddle east, into the wind, then scoot over an inches-deep lagoon toward the southernmost point, where a gap in the reef produces breaking waves. The sun and Hann emerge, and I study him catching rides for an hour. I have never paddle-surfed, but I battle to manoeuver my board into position. Finally, overcoming my fear of the sharp coral, I pivot onto a cresting wave. It immediately sends me flying, the leash tethering my ankle to the board comes undone, and I bob in the shallows as Hann retrieves my SUP.

Kimike Smith leading a paddle on Tobacco Caye

As we paddle back to the lodge, my classmates wave from the beach bar next door, where a crimson happy-hour sunset and a couple rounds of mockery await.

In the morning, Captain Balls ferries us to a nearby chain of mangrove islands. Mustering on our boards out of the wind, Hann shows us some effective SUP turns, then leads us on to a maze of channels through the dense mangroves that buffer the coastline and coral from erosion and sediment, providing a nursery for dozens of species, including manatees, nurse sharks and herons.

Halfway across an open bay, we are hit by a blustery rain squall. Paddling hard (vigorous effort, zero technique), I touch ground on a tiny caye with a single house. Smith banters in singsong Kriol with the island’s watchman, gets permission to stash our boards on the sand, and we hop in the boat to zip home for lunch.

Eating in South Water Caye

Meals at the lodge are taken family-style—shrimp in coconut mustard sauce, honey-glazed plantains with cinnamon, barbecued snapper—and offset every calorie burned on the water.

Dawn on Day Three brings an easterly of 18 knots or 33 km an hour—too strong to paddle across the gap in the reef on the 10-km passage to South Water Caye. I had been looking forward to the prospect of self-propelled travel to our base for the next three nights, but my chagrin at boating instead of boarding vanishes when we dock at the International Zoological Expeditions lodge. Palm-canopied pathways lead to breezy cabanas in the mangroves, reggae drifts over from the bar and the biggest danger here, we discover, is the resident pup, Reef, playing fetch with a whole coconut and dropping the heavy fruit at our feet.

On South Water Caye, we alternate between near-shore training in the glass-smooth leeward sea off the west side of the island and short excursions: a sail-assisted SUP to an adjacent caye; a visit to the Smithsonian reef ecology research outpost on one-acre Carrie Bow Cay, which hosts scientists from around the world (and has an outhouse with a killer view); snorkelling amid a rainbow of iridescent fish in a coral garden.

There’s a 20-knot tailwind on our last day—a perfect push for the 10-km crossing to Billy Hawk Caye, and a chance to test the skills we’ve been learning all week. The swells aren’t huge, but there’s no land in sight for reassurance, and it takes a few minutes to settle into the rolling seas.

Looking over my shoulder and timing the two-foot waves, shifting into a sideways surf stance, I manage to ride and link a few crests. The water’s energy gives me a rush, like dropping down a steep pitch on a ski hill; it feels like I’m flying.

Bar on South Water Caye

Back on South Water, still feeling the sway of the ocean, we toast one another with fresh coconuts spiked with rum.

That night, the moon is a sliver from full and I go for one last paddle. It’s so bright, I can see the board’s shadow on the sandy sea floor. Schools of fish dart away and bioluminescent worms wriggle in patches of sea grass. I practice my forward stroke and do a few sweep turns, then close my eyes and drift in the warm salt air.

Getting there: WestJet flies to Belize three times a week from Calgary and Toronto.